What is this article about?

The implications and challenges of central bank digital currency (CBDC) and the dominance of intermediated payment systems.

Why is it important?

It highlights the risks and strategic concerns of relying on private payment systems and the potential for CBDCs to offer a more secure, autonomous alternative.

What’s next?

The future involves addressing the need for institutionally supported digital payments that do not depend on intermediaries.

Payments are fundamentally about telecommunications, not banking. And yet, consumer-facing banks have built a profitable business model on payments, shifting away from their core business and introducing a new form of systemic risk. Seeing the danger to monetary policymaking resulting from using private money and payment systems beyond their reach, central banks worldwide have begun to explore central bank digital currency (CBDC). However, the experience central banks have with retail payments is usually limited to overseeing gross settlements among banks. Modern retail electronic payments generally involve transfers between two accounts, historically governed by the same logic that gave rise to ISO 20022: banks execute transactions at the behest of their customers. Until the past decade, most retail transactions were done using cash and, therefore, did not follow this pattern, but the rise of the digital economy has changed everything.

Concerns over strategic autonomy in Europe

Together, Visa and Mastercard carry a growing share of retail payments in Europe, raising legitimate concerns about strategic autonomy for Europe and the ECB. It is easy to see why EU regulators might be concerned about sending the proceeds from duopoly rents abroad, as well as the possibility of future tariffs or restrictions by the US government on services in Europe. Consider the ECB strategy for CBDC: clone the prevailing intermediated services and have the state or its delegates run them instead. Avoid facing the powerful lobbying force of the prevailing networks, which has become a flashpoint in politics across the Atlantic, even if that means failing to coordinate with private-sector banks. The grand vision is a local system for payment services provision within the jurisdiction of EU regulators, in contrast to foreign systems that could potentially undermine the interests of EU businesses, EU citizens, or both. But while this approach might achieve the objective of protecting the EU from foreign threats, it completely misunderstands the threat posed to the interests of individuals and households by the retail payments milieu, irrespective of its operators. Currently, there is no way for individuals and households in the EU to engage with the digital economy using assets that they possess and control, and to transact on their own terms, away from the risk of profiling not only by governments but also by private sector actors, which are incentivised to use their position not only to collect transaction fees that might accrue to foreign shareholders and governments, but also to harvest transaction data to profit from the systematic profiling (and potential censorship) of end-users. If the European Parliament were serious about safeguarding the use of cash, as it claimed in its Single Currency Package proposal last June, then why would it support the development of a “fully offline” version of CBDC that would compete with cash, undermining the efficiency of both?

Source: ECB, Banque de France

The dominance of intermediated payments

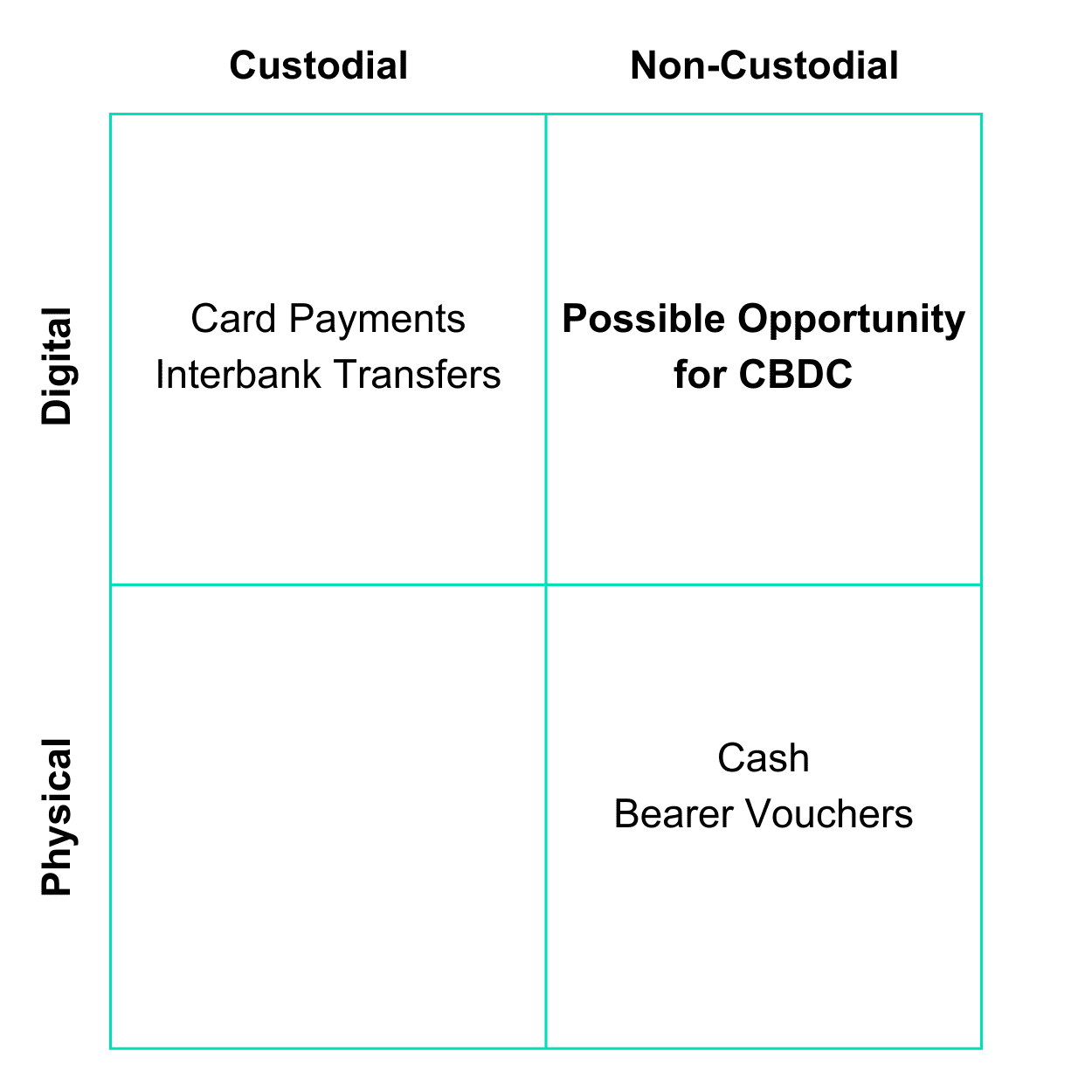

Whatever the ECB and other central banks might think, the problem is not that Visa and Mastercard have come to dominate the market for intermediate payments but that intermediated payments have come to dominate the market for payments, full stop. The simple reality is that most electronic payments today are intermediated by asset custodians on both sides of the transaction, and

this has led some policymakers, technologists, and others to assume that all electronic transactions must be intermediated as a matter of necessity. Indeed, ISO 20022 is predicated upon the assumption that electronic transactions will always involve custodians managing account balances on both ends. However, the crisis introduced by digital currency results from a failure of imagination, not a failure of technology. It is technically possible to hold digital assets outside of custodial accounts, just as it is possible to hold physical assets outside of safe deposit boxes, although many proposals for digital currency and payment systems, in general, dismiss this possibility in a perfunctory way. They assume that accounts are more efficient, presumably reasoning that intermediaries are better equipped to manage value and that it would be irrational for households and businesses to choose not to incur counterparty risk or the risk that their assets might not be available on demand. Why would anyone use cash when credit will do?

The inefficiency of cash in modern economies

The argument that cash is an inefficient form of money has been explicitly argued by CBDC proponents in the governments of the United States and China in recent years, but the argument is much older than that, dating at least as far back as 1998 when Fed governor Narayana Kocherlakota argued that it would be better for the world to use credit rather than cash, subject to the assumption that sharing more information about the identities and history of transacting parties would reduce friction. Two years earlier, the Financial Action Task Force issued a recommendation that national governments should seek to replace cash with more “secure” modes of transferring value because cash promotes crime, and more surveillance must be the solution. With card payments, private sector platform operators and governments alike can engage in profiling and censorship according to their interests, and it is difficult to imagine any institution intentionally relinquishing such power.

Source: ECB

Concerns from private-sector banks about CBDCs

Private-sector banks have expressed concerns that CBDC threatens their businesses because it would undermine their role as intermediaries. However, this assumes that CBDC would compete with bank deposits; such an argument is preposterous. If CBDC were to be held outside accounts, it would not be rehypothecated, so it would not earn interest. Parties seeking a return would be better off depositing money with a financial institution. But the concern about disintermediation belies an existential question: why do households and businesses deposit money with banks, anyway? Is it really about putting their money to work, the classical motivation for banking, or is it actually about access to payment services? Are banks failing to deliver value to their customers that could not just as easily be delivered by telecommunications providers or other technology firms operating at the behest of central banks instead?

The foundational raison d’etre and precondition common to all digital currency is the idea that digital assets can be held directly, outside of custodial accounts. An account by any other name would lack the most salient feature of this new innovation. And indeed, many of the so-called “wallets” proposed by banks and technology firms are just that. If a payer must invoke his or her asset custodian in a transaction, then the custodian must have possession, control, or both. To the extent this is true, the value of digital currency is lost, and sceptical groups such as the UK House of Lords are right to ask whether CBDC really is a solution in search of a problem.

The foundational raison d’etre and precondition common to all digital currency is the idea that digital assets can be held directly, outside of custodial accounts. An account by any other name would lack the most salient feature of this new innovation. And indeed, many of the so-called “wallets” proposed by banks and technology firms are just that. If a payer must invoke his or her asset custodian in a transaction, then the custodian must have possession, control, or both. To the extent this is true, the value of digital currency is lost, and sceptical groups such as the UK House of Lords are right to ask whether CBDC really is a solution in search of a problem.

Unfortunately, the trouble with dismissing digital currency outright is that there really is a problem to solve. Digital payments have been with us for decades now, and, as of 2024, there remains no institutionally supported way for households and businesses to pay each other without asking a privileged gatekeeper to do it at their behest.

Read more Payments Intelligence

Merchant survey 2025: Navigating the payment innovation divide

A 2025 survey of UK retailers reveals how payment challenges and innovation priorities are shaping merchant strategies across the sector.

Open banking survey 2025: Insights from 500 UK SMEs

UK SME survey shows open banking intrigues merchants with faster, cheaper payments, but gaps in awareness and security fears slow adoption.

Offline settlements with a digital pound: Lessons from the BoE’s report

The Bank of England’s offline CBDC trials show it’s technically possible—but device limits, fraud risks, and policy gaps must still be solved.