Chargebacks are a pain point for merchants which can sap revenue, cause reputational damage and in extreme cases lead to the loss of processing privilege. Yet their existence underpins consumers’ confidence in using their cards, providing recourse against fraud and unscrupulous sellers.

Since the acceleration of the shift to e-commerce brought about by the pandemic, more consumers have become aware of their rights and the chargeback process. This understanding, though, is often imperfect, leading to many chargebacks filed erroneously which merchants end up on the hook for.

“It’s not just the financial impact that takes its toll, there is a lot of unseen time and admin on the side of the business that goes into these disputes/claims,” says Violeta Stevens, managing director of Union Hand Roasted Coffee.

Mastercard estimates the cost of chargebacks will reach $1 billion in 2023, with merchants bearing most of the cost. The company, along with fellow payment titan Visa, has made changes to try to reduce merchants’ chargeback woes – but there’s plenty merchants themselves can do to minimise the amount of errant chargebacks coming their way in the first place, and to deal with the ones they do receive in a more efficient manner.

Around 0.6% of transactions are chargebacks, according to payment software provider Clearly Payments.

The US-based payment processing company Shift puts chargebacks for the retail industry at about 0.5%, with ratios higher for digital service providers, and exceeding 1% for providers of financial services and education services (others estimate these figures lower).

Between 2019 and 2021, annual Visa card-not-present sales grew 51% and disputes grew nearly 30% globally, per the company’s internal data.

At around a 1% chargeback rate, merchants are at risk of losing out more than their revenue. Chargeback ratios at which merchants face being put into remedial programs – or cut off entirely – by payment providers vary, but it’s at this proportion where serious problems begin to occur.

One way to reduce the chargeback rate is to contest those that have been wrongly made. Around 68% of chargebacks are successful, meaning that 32% of chargeback disputes fall in favour of the merchant, claims Payment Cloud citing data from Chargebacks911.

Unfortunately, contesting chargebacks is very expensive, specialised and time-consuming work. The money spent contesting a chargeback successfully can easily be ten times the value of the relevant transaction.

There are numerous steps merchants can take on a non-technical level to reduce their chargeback rate, mainly by stopping them occurring in the first place.

The first, and most obvious, is to provide good customer service so that people whose goods are lost in the post, receive damaged goods, or experience sub-standard services can access refunds rather than initiating a chargeback.

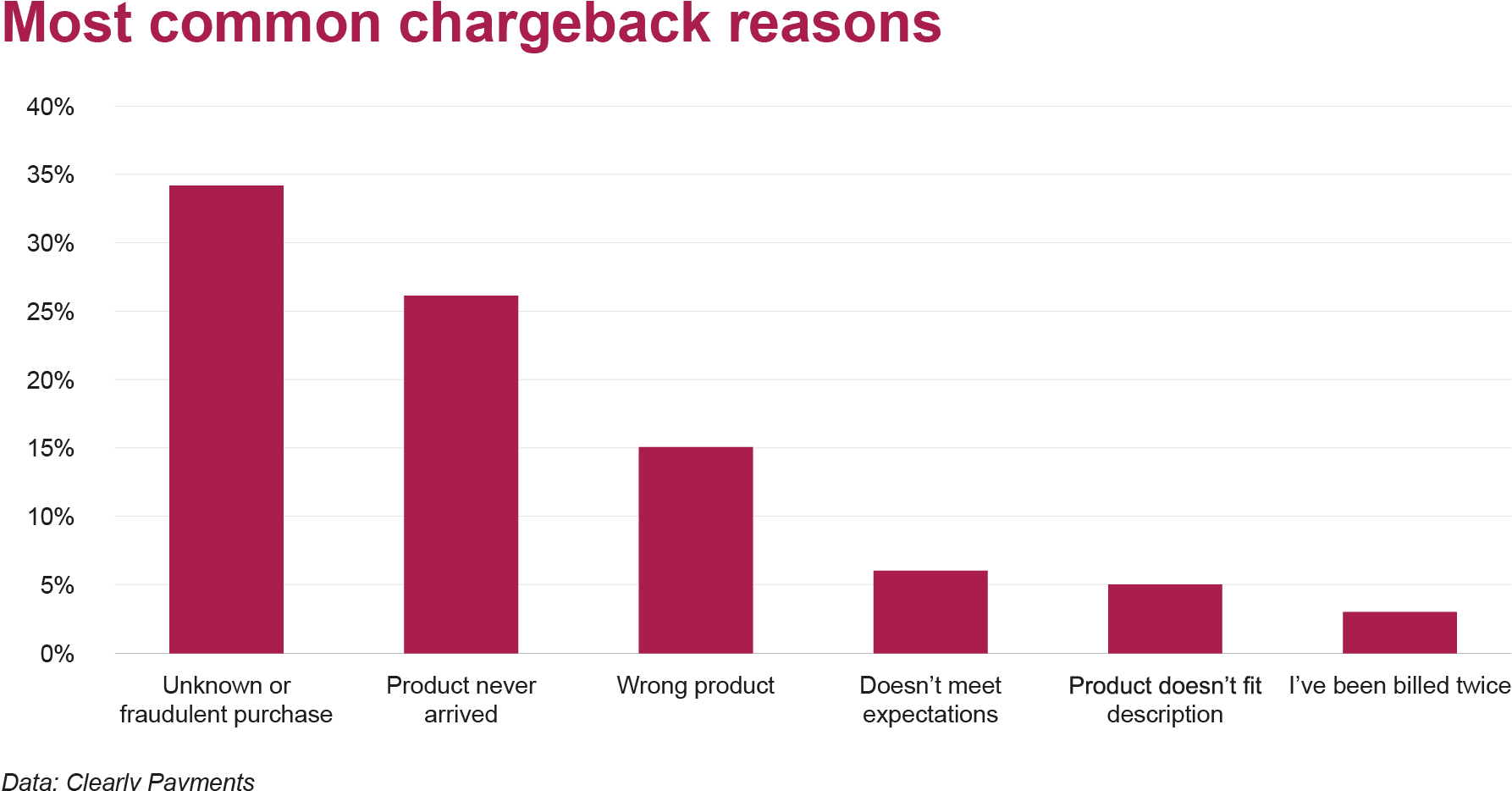

Products not arriving, the wrong product arriving, products not meeting expectations or not fitting the description account for 53% of chargebacks, according to Clearly Payments.

Some chargebacks (3%) are initiated because a customer is billed twice. With vigilant customer service and prompt refunding, some of these can be eliminated.

Normal people don’t know that a chargeback incur significant costs for merchants. Many don’t even understand what a chargeback is. But faced with a website FAQ page, no contact details and perhaps a particularly obtuse chatbot, rather than someone who will promptly answer a message or a phone call, filing a chargeback becomes an easier option.

“In the States, you can literally click a button, and you file a chargeback,” says Monica Eaton, CEO at Chargebacks911, saying later that some people see it as a “refund button”.

The most common single reason people file chargebacks (34%) is unknown transactions on their bank accounts. If these transactions are fraudulent, the chargeback is legitimate, in which case the chargeback system is serving its purpose.

But all too often, this isn’t the case – customers are just confused. Merchants can reduce this confusion by ensuring payment descriptions which appear on customers’ bank statements are clear. Misunderstandings here are a top main reason for incorrect chargebacks stemming from unrecognised transactions.

“One of the reasons cardholders often raise a dispute is because they don’t recognise a transaction on their statement or that app,” says Mark McMurtrie, an independent payments consultant.

“Some simple reasons for this might be a geographic one, the transaction appears for a certain city or town that they think they have never been to; the transaction may be flagged on their statement with a merchant name that they do not recognise; or, a third option is the merchant name is abbreviated so much that it cannot be distinguished.”

The latter case, he says, goes hand in hand with the growing use of payment facilitators who represent multiple merchants using a single name.

Eaton adds: “The descriptions that describe what the payment was used for, if you log into your banking app, often you only see a portion of that description,” says Eaton. “And it’s very difficult to recognise.

“We need to advance our technology to keep up with the changing times, because up to 75% of these chargebacks are literally accidentally filed.”

The author’s experience

Joe Stanley-Smith

I haven’t been to Glasgow for several years and I don’t drink coffee, yet the payment description of a recent transaction to a Patreon-like crowdfunding website makes it look like my card has been used in a Glasgow coffee shop.

I didn’t know the website (a Patreon-like crowdfunding website called buymeacoffee.com) was based in Glasgow when I made the payment. This payment description doesn’t mention who I was even donating to – it could certainly be improved to reduce the risk of a customer mistaking it for fraudulent behaviour.

By contrast, the transaction with thetrainline.com is unambiguous, and provides a reference number to follow up if necessary.

So, we’ve dealt with upset customers and confused customers. Now, it’s time to deal with customers who lie.

Knowingly filing a chargeback for a transaction that wasn’t made by a fraudster is known as first-party fraud, or friendly fraud.

Eaton posits that consumers who make a legitimate chargeback can become tempted, upon learning first-hand how easy the process is, to do it again illegitimately. And, given that contesting a $100 chargeback can cost the merchant ten times that in legal fees, they’re usually getting away with it.

It can be all too easy for a customer to simply pretend a purchase didn’t arrive and file a chargeback.

“We’ve seen customers claiming that products are damaged, which means we have to spend the time checking through our systems and sending a replacement, with no evidence that the products are definitely damaged,” says Stevens.

“Likewise, we also have experienced people claiming that they simply haven’t received any coffee, when we know the coffee has been sent straight away after their order.”

There are also less blatant instances of friendly fraud. Perhaps a child bought hundreds of pounds more Fortnite add-ons than had been agreed. Or a teenager didn’t realise when using their parent’s credit card to pass an online age check that their bank statement would show a purchase from www.sexyschoolteachers.com. Feeling these instances beyond their control, a parent could just file a chargeback.

It’s still fraud, and since the pandemic it has been growing. Merchants have a right to be annoyed by it, and to demand solutions to it.

Eaton says that the philosophy among companies used to be to accept customers’ version of events and not contest chargebacks – but as the frequency of fraudulent chargebacks increases, and the bad behaviour becomes self-reinforcing, this philosophy is changing.

Crystal’s experience

Crystal, 33, from England, says she is sure these transactions from her bank statement are fine but can’t tell you exactly what they are.

She knows about chargebacks, and almost filed one once before realising the transaction she was concerned about had in fact been made by her.

“Most of the time it’s just about the transaction description or vendor description not matching what I thought,” she says.

Despite working in financial services, she was unaware that a chargeback costs a merchant more than the amount refunded. She would file one if she was “genuinely worried”.

It’s against this backdrop that the world’s leading card payment providers, Visa and Mastercard, have introduced new tools for tackling card-not-present fraud and, specifically, friendly fraud. Mastercard has made a number of changes through its Mastercon Collaboration dispute management platform. Visa’s most recent first-party fraud-related changes come through its Compelling Evidence 3.0 standard (CE3.0).

Under CE3.0, businesses can provide records of previous undisputed transactions, made using the same payment method, with a matching IP address or device ID. The transactions must be between 120 and 365 days old, and if the IP address and device ID don’t match on all three transactions, the three must share an additional corroborating element, such as shipping address or account login.

“These changes are an important part of Visa’s strategy to fight all types of fraud across its network and protect businesses,” Visa told Payments Review.

“At the same time, Visa’s strong customer protection through its Zero Liability Policy means customers won’t be held responsible for unauthorised or fraudulent charges made with their Visa credentials. They could also get their money back when they genuinely don’t get what they have paid for, where the seller won’t refund.”

Visa said it’s too soon to share feedback it’s received on the implementation of CE3.0, which only went live in mid-April.

Mastercard’s anti-friendly fraud measures went live earlier. The company didn’t respond to requests for comment from Payments Review.

Sanjay Bibekar, director at PwC in London, said the impact of the changes is “yet to be seen”.

While McMurtie describes friendly fraud as akin to “digital shoplifting”, he adds that “it needs to be managed sensitively to respect that there may be issues of vulnerable customers where care needs to be taken”.

A chargeback on a significant deposit on a gambling website, for example, could be an indicator that a person has spent – and lost – more money than they can afford to, and is resorting to fraud to try to recoup their money or hide it from a loved one. Studies from around the world show that problem gamblers are significantly more likely to commit suicide than the general population.

In addition, it’s important to contextualise the impact of friendly fraud. In the same report in which it estimated chargebacks will cost $1 billion in 2023, Mastercard said there is $5.9 billion of card-not-present fraud taking place annually in the US alone.

It’s a similar story to out-of-work benefit or disability benefit fraud. Lots of media attention falls on cases where people claim illegitimately because it’s emotive for taxpayers or, in this case, merchants. When you delve down into the figures, though, under-claiming is far more common and worth far more money – but receives far less attention.

While some consumers are taking advantage of the chargeback system, or unwittingly misusing it, there are many more people who, for whatever reason, do not avail themselves of their right to make chargebacks when they fall victim to fraud.

McMurtrie says friendly fraud is “an issue rather than the issue”.

“Fraud is a moving target. And I’ve always used the analogy of like a balloon, you squeeze in one place, it pops out another place. What we’re seeing is fraud always takes place at the easiest options.”

In recent times, the use of pre-dispute services has made disputing chargebacks easier. These are alerts sent to tell the merchant that a dispute has been raised between the cardholder and the card issuer (generally the cardholder’s bank).

This also provides an opportunity to update their fraud defences. If, for example, a customer’s account has made a large amount of purchases and a pre-dispute has been raised, it can be an opportunity to hold other goods due to be shipped to that account, to prevent the impact of fraud worsening.

On the subject of the chargeback, it’s at this point that merchants have to act quickly, usually by either refunding the consumer to prevent the chargeback and associated cost, or sending the appropriate information to the payment processor to dispute the chargeback.

But while it’s in merchants’ interest to be on top of chargebacks, McMurtrie says they are actually the party with the most work to do to in this area.

“The stakeholders who are currently least advanced in the chargeback process are the merchants. Merchants still lack information about the chargeback process, and are reliant on the communications and tools that they are offered by their acquirer.”

Many merchants still use inefficient, paper-based systems or email-based systems to file them. Given the advancement in technology, and the level of not just digitalisation, but automation present within other areas of the payments industry, relying on emails and spreadsheets to keep up with deadlines is borderline anachronistic.

Nowadays, merchants should be aiming to avail themselves of application programming interfaces (APIs) to integrate chargeback dispute management into their IT infrastructure and even automate parts of chargeback defence by leveraging other parts of their data.

But there are also off-the-shelf tools and systems available to help merchants to automate and improve their dispute management processes.

Given the complexity of the chargeback process, and the expertise, processes and vigilance required to deal with them efficiently, more and more merchants are deciding to outsource parts of the process to specialist service providers.

“There is a trend for issuers and acquirers to outsource elements of the chargeback process to specialists,” says McMurtie.

“What we have seen, is that the industry as a whole, there’s a lot of value-added services that are piggybacking on the chargeback pain point,” adds Eaton. “It’s very painful[…]. When you have a lot of pain, then it drives demand for more efficient solutions to avoid chargebacks altogether.”

Such service providers tend to work through leveraging information from Ethoca and Verifi – which act as pre-dispute platforms for Mastercard and Visa, respectively – and overlaying their own technology and knowledge.

“When a chargeback happens, a consumer or their bank end up contacting the schemes with a disputed transaction,” says Eaton, whose company Chargebacks911 is an example of such specialist service providers.

“That transaction can flow through our platform to notify the acquiring bank. And then the acquiring bank notifies the merchant, the merchant decides either to challenge or contest the case and submit documentations or to accept liability on the case.

“We provide the technology that sits in the middle and help automate all of the really messy workflows and cycles. And with chargebacks, there’s hundreds of different rules, compliance rules, every single region, every card type, every payment method has different rules and flows.”

McMurtie notes that not all merchants are going down this route – “some still maintain systems in-house” – but that the trend of outsourcing to external service providers is “accelerating”.

With an eye on the future, it’s worth mentioning that no chargeback-like mechanism currently exists for open banking.

“I think open banking will not be implemented by the mass of merchants until an effective dispute process is implemented in order to be able to protect the merchant interest and the card holders interests,” says McMurtrie.

“That process should look to build from the learnings of the card payment chargeback process, but implement a cut-down version with less inefficiencies.”

However, PwC’s Bibekar has a different opinion. “Open banking is different and typically safer than card transactions, in a way that it relies on direct bank-to-bank transfers using APIs, requiring customer consent, hence the need for chargebacks will be limited,” he says.

Tony Craddock, founder and director general of The Payments Association, adds: “We want to see a chargeback mechanism, we want to see dispute resolution service that protects all open banking services stakeholders now.”

The Payments Association

St Clement’s House

27 Clements Lane

London EC4N 7AE

© Copyright 2024 The Payments Association. All Rights Reserved. The Payments Association is the trading name of Emerging Payments Ventures Limited.

Emerging Ventures Limited t/a The Payments Association; Registered in England and Wales, Company Number 06672728; VAT no. 938829859; Registered office address St. Clement’s House, 27 Clements Lane, London, England, EC4N 7AE.

Log in to access complimentary passes or discounts and access exclusive content as part of your membership. An auto-login link will be sent directly to your email.

We use an auto-login link to ensure optimum security for your members hub. Simply enter your professional work e-mail address into the input area and you’ll receive a link to directly access your account.

Instead of using passwords, we e-mail you a link to log in to the site. This allows us to automatically verify you and apply member benefits based on your e-mail domain name.

Please click the button below which relates to the issue you’re having.

Sometimes our e-mails end up in spam. Make sure to check your spam folder for e-mails from The Payments Association

Most modern e-mail clients now separate e-mails into different tabs. For example, Outlook has an “Other” tab, and Gmail has tabs for different types of e-mails, such as promotional.

For security reasons the link will expire after 60 minutes. Try submitting the login form again and wait a few seconds for the e-mail to arrive.

The link will only work one time – once it’s been clicked, the link won’t log you in again. Instead, you’ll need to go back to the login screen and generate a new link.

Make sure you’re clicking the link on the most recent e-mail that’s been sent to you. We recommend deleting the e-mail once you’ve clicked the link.

Some security systems will automatically click on links in e-mails to check for phishing, malware, viruses and other malicious threats. If these have been clicked, it won’t work when you try to click on the link.

For security reasons, e-mail address changes can only be complete by your Member Engagement Manager. Please contact the team directly for further help.