Merchant survey 2025: Navigating the payment innovation divide

A 2025 survey of UK retailers reveals how payment challenges and innovation priorities are shaping merchant strategies across the sector.

16 June 2025

by Payments Intelligence

What is this article about?

A Bank of England experiment proving that offline payments with a digital pound are technically feasible, but complex.

Why is it important?

It highlights major trade-offs in security, privacy, and policy that must be addressed before offline CBDC payments can scale.

What’s next?

Policymakers must resolve governance questions while the industry prepares for potential integration and standard-setting.

The Bank of England (BoE) has demonstrated that it is technically feasible to carry out offline payments with a digital pound. The experiment was carried out in partnership with Thales, Secretarium, and Consult Hyperion, demonstrating both the technical plausibility and the layered complexities of enabling a central bank digital currency (CBDC) to function without internet connectivity.

For payments leaders, the findings are not simply a technical footnote. If implemented, offline CBDC capability could introduce new consumer behaviours, shift merchant requirements, and alter the economics of digital payment acceptance. Simultaneously, it would entail trade-offs in security, user experience, and operational design that demand careful scrutiny across the industry.

Despite the success of the experiment, no final decision has been made on whether to implement an offline payment functionality if a digital pound were launched.

The project assessed whether it was feasible to enable payments between parties who had no access to the CBDC network at the time of transaction, a scenario often triggered by poor connectivity or service outages. This “device-to-device” approach would allow smartphones or smart cards to store value locally and initiate peer-to-peer (P2P) or person-to-business transactions offline.

All solutions trialled were able to achieve “final and irrevocable offline CBDC payments,” meaning that once funds were transferred, the payee could spend them immediately, without needing to reconnect to the central ledger. These solutions functioned by pre-loading funds onto user devices via an intermediary, creating a separate offline balance within the digital wallet.

However, this structure introduced practical constraints. Offline functionality was contingent on the user having pre-downloaded funds, limiting its spontaneity during unexpected outages. Furthermore, wallets had to manage dual balances (offline and online), requiring users to actively choose between them when transacting. These mechanics underscore the critical role of user interface design in ensuring ease of use does not become a barrier to adoption.

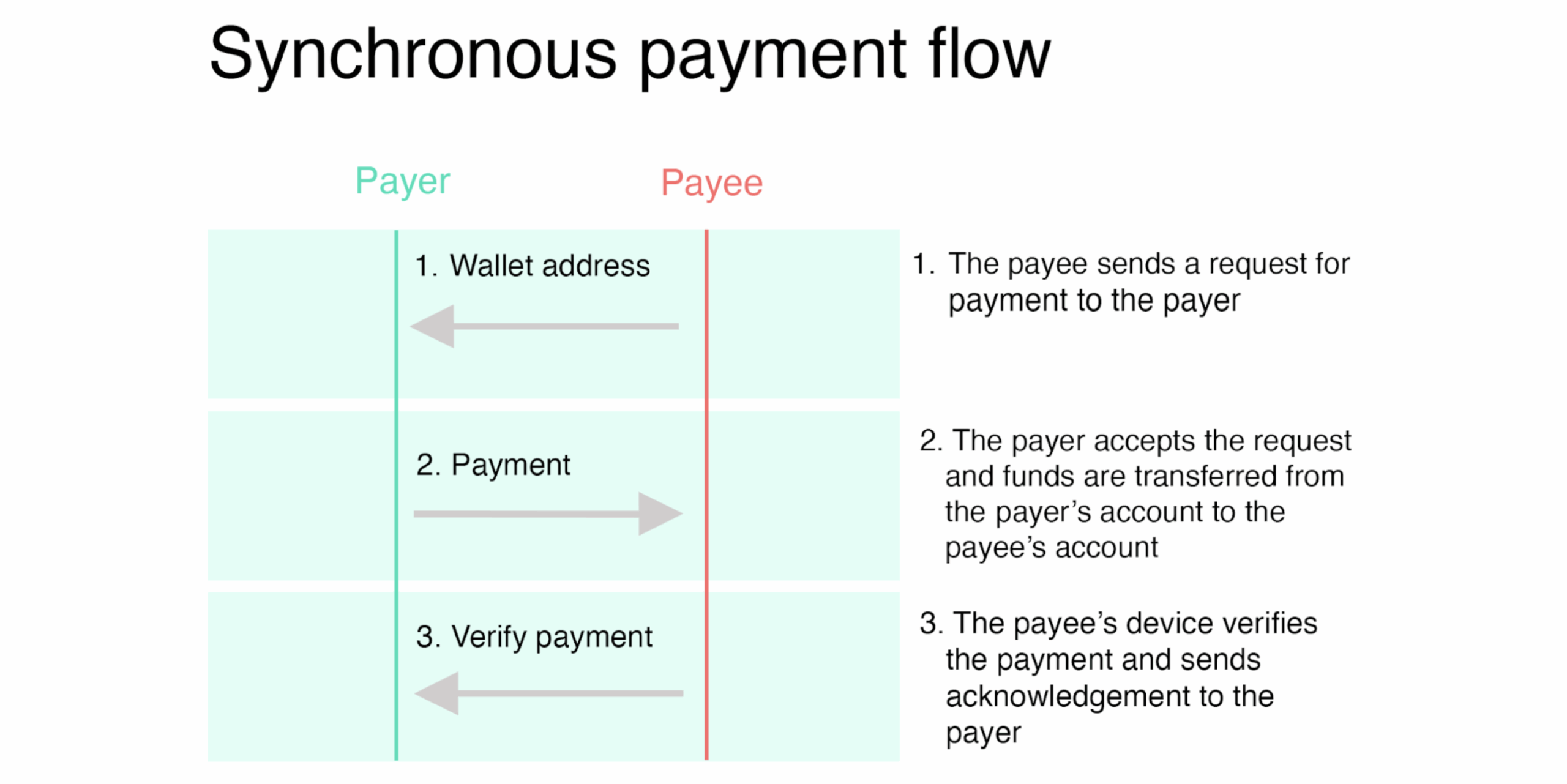

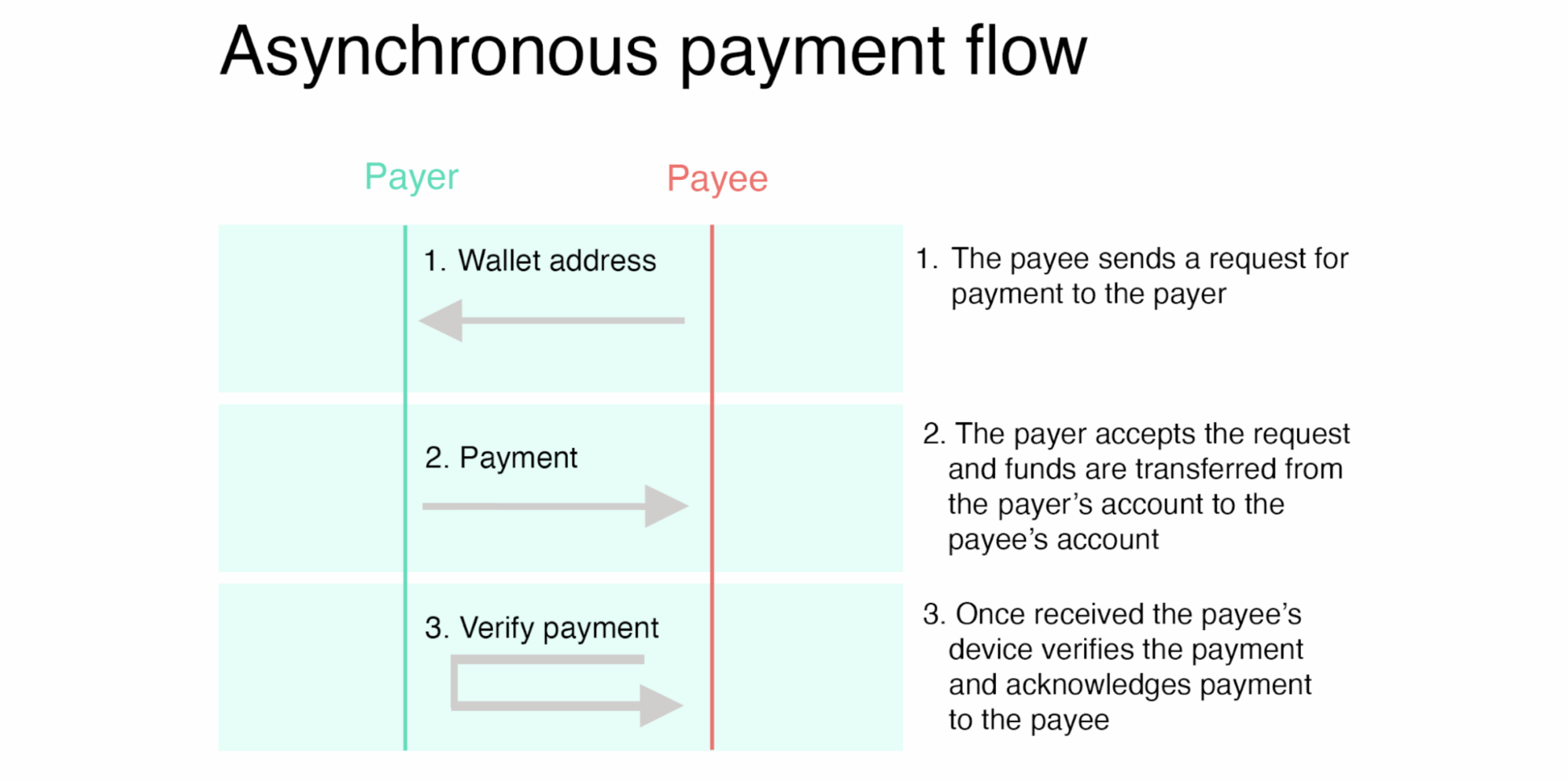

Two distinct payment flows were tested:

Asynchronous: where the payer sends funds using the payee’s wallet ID, without the payee being present. The payment does not need to be sent to the payee’s device directly, and could be generated as a QR code, sent via SMS, or over email, for example. As the payment message includes the issuer’s public key, the payee’s device can verify the transaction upon receipt of the payment.

While asynchronous payments may appear more flexible, they introduce a major risk: irrecoverability. Once sent, funds are deducted from the payer’s device regardless of whether the payee ever receives them. In contrast, the synchronous model offered built-in safeguards, allowing for the recovery of funds in failed transactions.

This distinction has real-world implications. Retailers and service providers may favour synchronous models to mitigate payment disputes. In contrast, asynchronous payments could serve niche use cases, such as ticketing or peer-to-peer gifting, if paired with clear user warnings and fallback mechanisms.

Offline payments, by definition, occur outside the purview of real-time ledger reconciliation, thus introducing the risk of double spending (attempting to spend the same funds twice). The experiment explored multiple countermeasures, chief among them being the use of Secure Elements: tamper-resistant chips that store cryptographic keys and transaction data on user devices.

The experiment tested two implementation models: one in which the Secure Element contained the entire transaction capability, and another in which only sensitive keys were protected. Both approaches provided a degree of protection, but neither was perfect. The reliance on Secure Elements introduces new dependencies for manufacturers and wallet providers, and if compromised, could open the door to widespread fraud.

Storage limitations within these chips also constrained transaction volumes and the complexity of risk detection algorithms. For instance, smart cards had markedly less capacity than smartphones, affecting their ability to track suspicious behaviours or store chains of transaction history.

As a secondary measure, online reconciliation was used to detect anomalies when users eventually reconnected. While effective for post-transaction monitoring, this retrospective approach cannot prevent losses, a point the BoE explicitly highlighted in its reflections. Preventive mechanisms must therefore strike a balance between protection and practicality.

To enable double-spend detection and fraud analytics, it is necessary to store a local transaction record. Solutions ranged from full, cryptographically linked transaction histories to minimal or even non-existent record keeping. Each approach carries trade-offs between security, privacy, and device storage constraints.

The experiment showcased privacy-enhancing technologies, including data pseudonymisation, confidential computing, and ephemeral key management. These tools allowed transaction records to be shared with intermediaries for verification, without exposing personally identifiable information to the BoE’s core systems.

In future implementations, privacy controls will likely be tailored to specific use cases, with varying levels of transparency and traceability. The Bank’s commitment to privacy-by-design remains a cornerstone of trust-building, particularly as offline capabilities inherently increase the complexity of data flows.

From a hardware integration perspective, the experiment tested several communication technologies to enable offline payments. Near-field communication (NFC) has proven effective for card-based transactions but has revealed ergonomic challenges, such as inconsistent reader placement across smartphones, which can affect ease of use.

Bluetooth Low Energy (BLE) offered more flexibility for phone-to-phone transactions and accommodated larger data transfers, making it better suited for Unspent Transaction Output (UTXO)-based payment models. However, BLE introduced latency and connection issues, particularly during the initial pairing process.

Ultimately, neither protocol emerged as superior; each complements different device types and use cases. This has implications for merchant acceptance infrastructure: payment service providers (PSPs) and terminal vendors will need to support diverse standards and develop hardware-agnostic interfaces.

Perhaps the most important finding of the experiment was not technical, but strategic. The feasibility of offline payments is deeply intertwined with policy decisions on liability, fraud thresholds, user protections, and regulatory oversight.

For instance, how much value can a user store offline? What are the obligations of wallet providers if a transaction fails or is fraudulent? Who bears the cost of reconciliation errors or counterfeit detection failures?

These are not engineering questions; they are matters of governance and legal architecture, and they must be resolved before any offline CBDC capability can be deployed at scale. As Diana Carrasco Vime, head of the Digital Pound Project, has reiterated, trust, security, and usability will determine whether the digital pound gains real traction.

For payments firms, the potential introduction of offline digital pound payments raises both opportunities and operational questions. Retailers could benefit from reduced transaction costs, particularly on low-value payments where card fees remain disproportionately high. Merchants in rural or connectivity-constrained areas may also see value in cash-like functionality delivered via digital means.

The integration effort will not be trivial. As the BoE’s point-of-sale proof-of-concept demonstrated, existing terminals require firmware updates, secure key management, and potentially new back-end APIs to accommodate CBDC payments, particularly in offline mode. The ecosystem will need to coalesce around standards to avoid fragmentation.

Meanwhile, startups and fintechs have a window of opportunity to innovate. From smart wallets that optimise offline balances to fraud detection algorithms and user-friendly interfaces, there is scope to lead the market in enabling trusted offline transactions.

The Bank has made clear that no decision has yet been taken on whether the digital pound will include offline functionality. However, this trial confirms it is technically viable, albeit not without cost or complexity. The next phase will require a policy assessment to determine the risk appetite and strategic goals of such a feature.

For industry leaders, this is a crucial moment to engage. As the BoE moves toward a potential build phase by the middle of the decade, the voice of the private sector will shape how user experience, merchant integration, and risk management are operationalised.

Offline payments may never be the default mode of digital pound transactions but their availability could serve as a vital backup option, enhancing resilience, inclusion, and trust in a rapidly digitising economy.

A 2025 survey of UK retailers reveals how payment challenges and innovation priorities are shaping merchant strategies across the sector.

UK SME survey shows open banking intrigues merchants with faster, cheaper payments, but gaps in awareness and security fears slow adoption.

The Bank of England’s offline CBDC trials show it’s technically possible—but device limits, fraud risks, and policy gaps must still be solved.

The Payments Association

St Clement’s House

27 Clements Lane

London EC4N 7AE

© Copyright 2024 The Payments Association. All Rights Reserved. The Payments Association is the trading name of Emerging Payments Ventures Limited.

Emerging Ventures Limited t/a The Payments Association; Registered in England and Wales, Company Number 06672728; VAT no. 938829859; Registered office address St. Clement’s House, 27 Clements Lane, London, England, EC4N 7AE.

Log in to access complimentary passes or discounts and access exclusive content as part of your membership. An auto-login link will be sent directly to your email.

We use an auto-login link to ensure optimum security for your members hub. Simply enter your professional work e-mail address into the input area and you’ll receive a link to directly access your account.

Instead of using passwords, we e-mail you a link to log in to the site. This allows us to automatically verify you and apply member benefits based on your e-mail domain name.

Please click the button below which relates to the issue you’re having.

Sometimes our e-mails end up in spam. Make sure to check your spam folder for e-mails from The Payments Association

Most modern e-mail clients now separate e-mails into different tabs. For example, Outlook has an “Other” tab, and Gmail has tabs for different types of e-mails, such as promotional.

For security reasons the link will expire after 60 minutes. Try submitting the login form again and wait a few seconds for the e-mail to arrive.

The link will only work one time – once it’s been clicked, the link won’t log you in again. Instead, you’ll need to go back to the login screen and generate a new link.

Make sure you’re clicking the link on the most recent e-mail that’s been sent to you. We recommend deleting the e-mail once you’ve clicked the link.

Some security systems will automatically click on links in e-mails to check for phishing, malware, viruses and other malicious threats. If these have been clicked, it won’t work when you try to click on the link.

For security reasons, e-mail address changes can only be complete by your Member Engagement Manager. Please contact the team directly for further help.